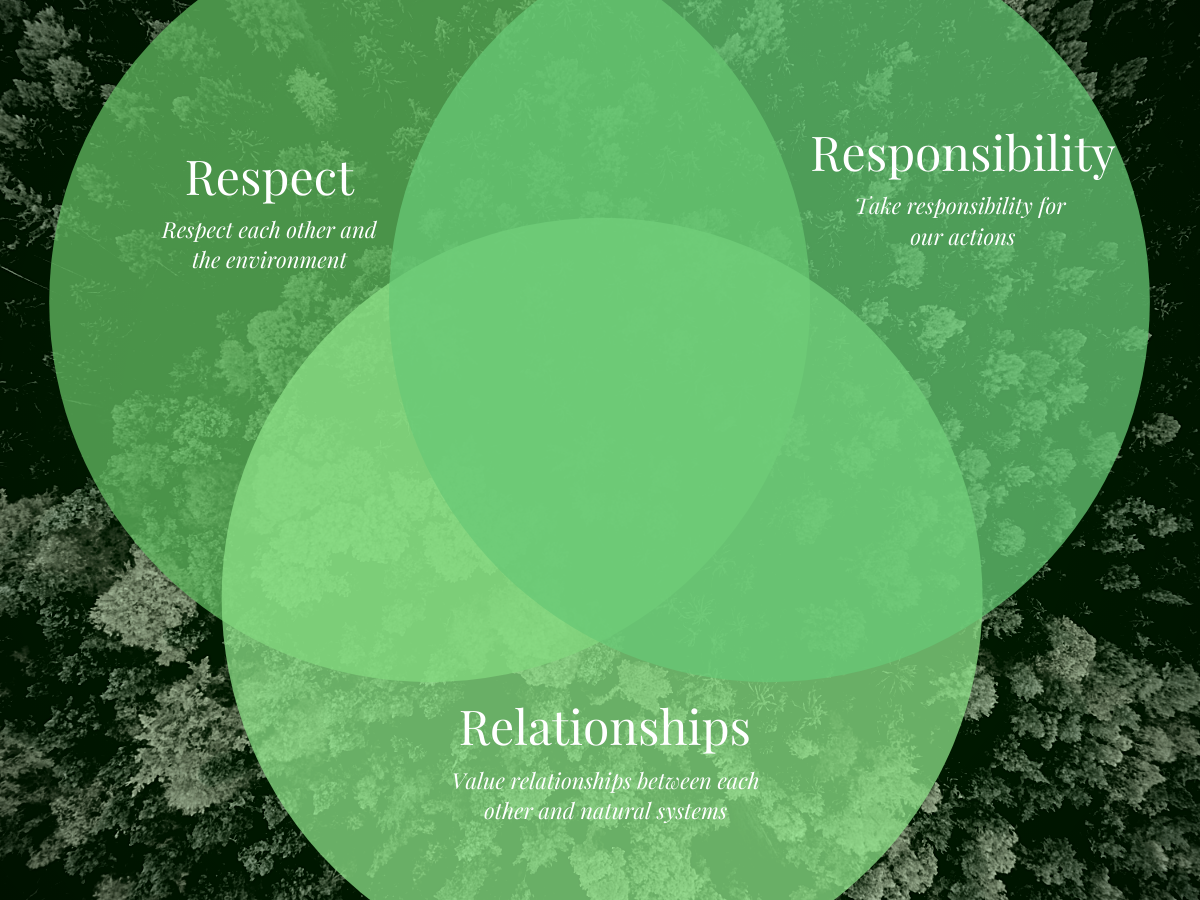

In order to work toward a future where we all have access to the resources we need to maintain a high quality of life, we need to be able to respect each other and our environment, take responsibility for our actions, and value relationships between each other and the systems that support us. This definition can be applied to a closely related topic that is appearing more frequently in national conversations: environmental justice.

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines environmental justice as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” Absent the fair treatment that all people deserve, some communities are forced to bear the burden of environmental externalities, such as air and water pollution and the impacts of natural disasters caused by human behavior.

While environmental protection might conjure images of exploring the great outdoors and visiting pristine National Parks, that has not been the experience afforded to all Americans. Instead, environmental practices rooted in race, class and gender, and in general a lack of respect for all people, resulted in disproportionate access to resources and placed additional burdens on Black and Indigenous communities and other communities of color.

Many of these inequities became institutionalized starting in the 1930s when government maps began outlining in red neighborhoods that were considered risks for investment - primarily those neighborhoods with Black residents – while predominantly white neighborhoods were highlighted in green to promote investment. Decades later, the lack of investment in these redlined neighborhoods has resulted in fewer green spaces, more pavement, and outdated and deteriorating infrastructure, making residents more vulnerable to extreme heat events and disruptions to safe drinking water access, among other environmental and health inequities.

The US EPA Office of Environmental Justice is hosting an online speaker series on environmental justice and systemic racism, with the first five sessions focusing on the impacts of redlining on environmental challenges. You can catch up on past sessions and register for future sessions on the series website.

One of the most visible outcomes of decades of environment injustice is in the waste and recycling industry, as landfills, toxic waste facilities, and even recycling processing facilities have historically been sited in communities of color, near Indigenous populations, and in low-income communities. But like many environmental challenges, many environmental injustice impacts are less visible.

Recent studies suggest that there is a gap between those who produce particulate matter emissions and those most impacted by them; while particulates are disproportionally produced by activities of White Americans, those particulates are more likely to impact Black and Hispanic Americans. A study published last month in Science Advances indicated that People of Color (POC), Black, Hispanic, and Asian Americans disproportionately experience exposure to particulates generated through industry, transportation and construction, among other sources, while White Americans are disproportionately exposed to particulates associated with coal electricity generation and agriculture.

The impacts of climate change such as heat waves, localized flooding, and other natural disasters are disproportionately impacting communities of color. Many of these environmental impacts have also been linked to disproportionate numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths in Black, Latinx, and Native American communities experiencing higher levels of air pollution and a lack of access to safe drinking water.

Environmental justice has become a national priority under President Biden, a sign that the administration is starting to take responsibility for past actions that have disproportionally harmed some Americans. Environmental justice is at the core of executive orders related to protecting public health and the environment and responding to climate change. The American Jobs Plan calls for the replacement of lead pipes and service lines, which are often found in drinking water infrastructure in communities of color, would invest in public transit, and seeks to reconnect neighborhoods divided by infrastructure development, among other initiatives.

In turn, EPA Administrator Michael Regan has announced four directives for EPA offices to incorporate into their efforts by strengthening enforcement of environmental and civil rights violations, directing resources to overburdened communities, and improving community engagement. As the federal agency most actively addressing environmental justice concerns, the EPA will likely be a model for how other agencies address this issue.

Here at the Environmental Finance Center, many of past and current projects address issues of environmental injustice. A series of food waste summits hosted by the EFC is elevating discussions on food deserts and the development of urban farms. We are also providing support for a Heartland Conservation Alliance water equity project, with a goal of producing a water equity road map for Kansas City. Our work with waste management and drinking water systems has provided support for testing for lead in drinking water at Kickapoo tribal school and daycare facilities, development of a sustainable financial plan for the Omaha Tribe’s Utility Department and provided training and resources for utilities operated by those tribes. You can learn more about these and other projects on our website.

But there is much more to be done throughout the nation to overcome decades of environmental injustices. As director of the EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice Matthew Tejada recently shared, we have to start by building relationships with the communities that are most impacted by environmental justice concerns so we can better understand their experiences and how to engage community members in finding meaningful and just solutions.