In 2001, the Lowell D. Holmes Museum of Anthropology at Wichita States University

organized an expedition into the Asmat region to collect the art for the museum's

collection.

Asmat expert and explorer Patti Seery, the museum’s former director, Jerry Martin,

along with a crew of Indonesian and Asmat people traveled the jungles and swamps for

six weeks to purchase and research the traditional and ceremonial art of the area.

They left the region with one of the largest and most important collections of Asmat

art now found in the United States.

Our deep gratitude goes to Paula and Barry Downing, who during a visit to Asmat in

1998 saw the wonderful beauty of their art and culture and agreed to fund the expedition.

Our gratitude also goes to Mr. Peter Bakwin, of Chicago Illinois for his generous

donation of his collection of over 100 important Asmat objects.

About the Asmat

In 2001, the Lowell D. Holmes Museum of Anthropology at Wichita State University had

the great fortune of being able to send an expedition into the Asmat region to collect

the art for the museum's collection.

The Asmat people live on the western half of the Island of New Guinea. This area,

called Papua, is the largest and least developed of all of Indonesia's 27 provinces.

Dense forest and mangrove swamp cover 85% of its area and parts of the interior remain

unexplored. Approximately 65,000 Asmat inhabit a vast landscape of Mangrove swamp,

meandering rivers, and a large expanse of mud, which extends for more than 175 miles

along the western coast of Papua.

The Asmat still live a very complex ceremonial life controlled by the need to maintain

harmony between the world of the living and the spirit world of the dead. During these

ceremonies a large variety of carvings and masks are used, each having their own function

and meaning. These ceremonial objects have long been famous because of their beautiful

intricate carving and often very large scale. Asmat art is also very rare. In the

past the Asmat were shielded from external influences by the harshness of their environment

and their fierce war-like reputation. Then in the 1950's missionaries and the Indonesian

Government began colonizing the area. The Asmat traditions of headhunting and cannibalism

ended in the 1970's, but very tight and restrictive controls over the Asmat remained

until 2002.

Few people were allowed to visit the area and very little Asmat art was collected

for collectors and museums. In 2001, the Lowell D. Holmes Museum of Anthropology at

Wichita State University had the great fortune of being able to send an expedition

into the Asmat region to collect the art for the museum's collection. Paula and Barry

Downing, who during a visit in1998 saw and understood the wonderful beauty of Asmat

art and culture, underwrote the expedition. The Director of the Holmes Museum, Jerry

Martin and an Asmat expert, Patti Seery, with a crew of eight Indonesian and Asmat

people traveled the jungles and swamps for six weeks to purchase and research the

traditional and ceremonial art of the area. They left the region with one of the largest

and most important collections of Asmat art now found in the United States. The only

other large Asmat collection found in the United State that was collected from the

field by trained anthropological museum personnel is the Michael Rockefeller collection

at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

The Ulrich Museum of Art and the Holmes Museum of Anthropology are very proud to present

for the first time to the public a selection of objects from the Barry and Paula Downing

collection of Asmat art. The exhibition will be held simultaneously at both museums

beginning on April 29, 2004 Spirit Journeys: the Art of the Asmat, the exhibition

at the Ulrich Museum will emphasize the artistic aspects of Asmat art. Featuring a

number of "Bis" ancestor poles" towering 20 feet in the air,"Wuramon" Soul Ships,

life sized body masks, drums and a host of other ceremonial objects. Spirit Journeys:

Ritual and Ceremony of the Asmat, the exhibition at the Holmes Museum, will feature

a replica of a men's ceremonial house with Asmat dancers, drummers and spirit masks

celebrating a traditional "Doroe" or "Farewell to the Spirits of the Dead" ceremony.

About the expedition

In the summer of 2001, Wichita State University became the first university in over

forty years to mount an extensive expedition to collect traditional art in the isolated

Asmat area of Southwestern New Guinea. The Asmat area comprises a remote, harsh environment

of mangrove swamps, jungle, mud and meandering river systems that provide the only

access to the villages. After their initial journey to Asmat, Paula and Barry Downing

made the decision to underwrite a Wichita State Asmat Expedition. Patti Seery, an

expert in Asmat art and culture, organized and led the expedition. Jerry Martin, Director

of the L. D. Holmes Museum of Anthropology, joined the expedition representing the

university. Over 950 diverse cultural objects were collected and documented thus forming

the basis of the Downing Collection of Asmat Art. WSU now possesses one of only three

significant collections of Asmat art found in the United States. The purpose of this

expedition was to gather a collection of Asmat objects that can be used by scholars

to learn about Asmat art and culture. Creating a research collection involves gathering

objects that have been used by the people and recording the items cultural context.

During the past 75 years museums have rarely undertaken the difficulties and cost

of acquiring large ethnographic collections that can provide the basis for academic

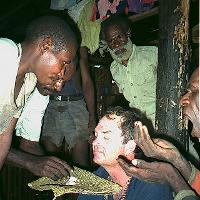

research, comparative studies and publications. The following photographs will illustrate

the expedition and explain the different steps in the process of museum field collecting.

These photographs were taken by Jerry Martin and Patti Seery during the expedition.

Planning and selecting the expedition crew

Before a museum expedition can take place, the people organizing the expedition need

to research the culture and determine what type of items will be collected for the

museum and which areas will be visited during the expedition. Once this has been accomplished,

the next step is to plan and implement the complex logistics for the trip based upon

the cultural regions selected and the amount of time allotted. Since there are 12

local dialects and almost no one speaks English in the Asmat region, the expedition

needed multiple interpreters to translate from the various dialects to the national

language of Bahasa Indonesian and English. During this stage, it is also necessary

to choose who will represent the museum's interests when selecting the items for the

collection and establish how the items will be sent safely from Asmat to WSU.

In the Downing Expedition, Patti Seery was the expedition leader, co-curator, logistics

organizer and interpreter. Her expertise in West New Guinea Island cultures and knowledge

of the area and language enabled the team to select a large number of culturally important

items that had been used in rituals or in everyday life and helped ensure the success

of the expedition. Jerry Martin, Director of the Holmes Museum of Anthropology at

Wichita State University, was the co-curator in charge of actual purchasing and training

any field personnel to record adequate information about the items.

Ronny Fordatkosu, a native Indonesian from Tanimbar Island, managed the bookkeeping,

helped with logistics, acted as interpreter and recorded traditional music. Ronny

was responsible for packing and shipping the objects from Asmat to Wichita. Other

important members of the expedition included two men to interpret the local dialects

into Indonesian, two boatmen and their respective assistants and a cook.

To navigate the myriad of rivers that traverse the Asmat region, the expedition used

one speedboat and two hollowed-out wooden longboats with 40 HP outboard motors. Other

equipment that was required for the trip included fuel and spare parts for the boats,

tents, rations of drinking water, tobacco for gifts and non-perishable food to supplement

the local staple diet of sago and first aid supplies.

Field collecting ethnographic objects

Once in the Asmat region, the expedition members needed to build rapport and create

mutual respect within the different villages they visited. By making their intentions

clear to the local people before collecting any items for the museum, expedition member

were able to establish good relations with them. The expedition maintained rapport

with the Asmat by approaching the toku adat or ceremonial leaders first, explaining

their motives for being there, offering tobacco, sharing food in their ceremonial

houses and establishing a fair price for the items they wanted to buy.

To maintain harmony and avoid creating any jealousy, the expedition members were very

careful to select objects from as many different individuals as possible. The goal

of the Downing expedition was to collect items that would reflect who the Asmat are

and how they live, so they selected a wide range of objects actually used in ceremonial

rituals and daily life. When selecting objects, the expedition members gave priority

to items that were made in the traditional way and had traditional motifs. Rarely,

they would purchase an object made for sale to highlight the differences between traditional

and tourist objects.

Recording cultural information

After selecting an item, the researchers needed to record where it was collected,

who was the maker or owner, when and where it was made and what materials were used.

Other important information included how the object was used, and any special cultural

or ceremonial meaning associated with the object. Recording this information allows

future researchers to recreate the cultural context of the object and learn about

the people who made it. It is important to note that museums must follow a code of

ethics when collecting. Doing so helps to avoid any complications with the local people,

maintains mutual respect and helps establish the integrity of the collection. For

example, the WSU Asmat Expedition made the decision not to collect any ancestor skulls

or human bones out of respect for the Asmat and to comply with import/export restrictions.

Transporting the collection

Many of the items were collected in remote villages far from the main base of the

expedition and involved extraordinary planning to transport them safely by longboat

back to Agats, the regional capital. Communication between the different longboats

of the expedition was non-existent once they separated from the main expedition team.

Fraught with worry about the safety of small wooden longboats at sea, enormous tides

and frequent breakdowns made each time a longboat reappeared a cause for celebration.

Packing and keeping the objects dry was especially difficult in the case of the extremely

large and spiritually charged ritual objects like the 33 foot long soul ship or wuramon.

Special taboos associated with their removal from the villages needed to be honored

and bis poles could never be transported at night. Offerings were always made to the

spirits at the mouth of rivers to ensure their safe passage. Once back in Agats all

the items were temporarily stored, tags were rechecked and rudimentary packing materials

were used to wrap the most fragile items. There was no safe and convenient way to

ship the goods out of Asmat to a place where they could be properly packed and fumigated.

The crew of a small inter-island sail boat was chosen to carry the collection without

the aid of modern navigation or any radio equipment to a major port on the island

of Java three weeks away by sea. Once the ship arrived, legal permission from the

authorities to unload and then export the goods outside the country became a bureaucratic

nightmare handled adroitly by Ronny. In Java, the 950 items of the Downing Collection

were properly insured and then loaded into 2 containers for their voyage to Wichita

State University. The collection left Asmat in July and arrived in Wichita, Kansas

in October of 2001.

Curating the collection

The conclusion of any field collecting expedition ends when the objects arrive at

the museum. Then, the time-consuming curation process begins. This involves cleaning,

preservation and conservation work, as well as cataloging the items. Since the items

in the Downing Collection had been wrapped and in-transit for three months, the preservation

process needed to start as soon as possible. Because most Asmat objects are made of

wood, natural pigments and plant fibers they need to be checked for insect infestation

and mold. Each object was kept in a plastic bag until it could be processed so contamination

from one object could not be transferred to another. Once an object was cleaned and

treated, condition reports, treatment forms and catalog sheets were completed. The

object was also photographed. Museum personnel and students have been busy with the

Downing collection since its arrival in October 2001. After almost three years of

hard work, a portion of the Downing Collection of Asmat Art was ready to be put on

exhibition. The nearly six year process of cleaning and cataloging the entire collection

was finished in July of 2007.