About braille

What is braille?

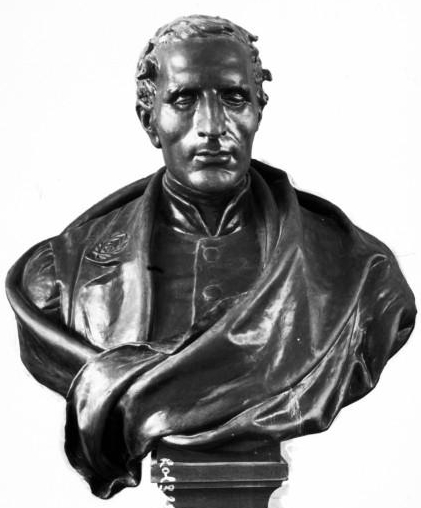

Braille is a tactile writing system developed in 1824 by Louis Braille for use by people with visual impairments. Originally based on a system called “night writing,” braille characters are formed using a combination of six raised dots arranged in a 3 x 2 matrix, called the braille cell. The number and arrangement of these dots distinguishes one character from another. Braille can be read on embossed paper or other material, or it can be read on refreshable braille displays.

Tactile graphics

Not all visual material is text. Some visual information, such as photos, can be made accessible by providing image descriptions. However, in the case of visuals like graphs and diagrams, it may be difficult or cumbersome to convert information to a written format. For situations like these, WSU creates tactile graphics by reproducing the essential components in a larger form, printing them on heat-sensitive paper (or “thermal paper”), and running the paper through a small heater. The parts of the paper with ink on then expand, creating images that can be felt.

Why braille?

Some may wonder whether braille is still necessary, given the existence of technology such as screen readers. While screen readers can help to improve accessibility for people with visual impairments, an audio format has some drawbacks. Braille, like printed text, allows the reader to more easily search and review information. Braille is also essential for literacy, education, and employment for people with visual impairments, as it provides information like spelling and punctuation that is lost in an audio medium.

Fast facts

- Braille is not a language — it is a writing system. There are braille codes for over 133 languages.

- When people produce braille, it is called braille transcription. When computer software produces braille, it is called braille translation.

- World Braille Day is January 4th.

- All ATMs are required to have braille keypads, including drive-through ATMs. This allows passengers with visual impairments to operate ATMs without depending on others. It is also possible to have a visual impairment that still permits driving under certain conditions.

- The word “braille” doesn’t need to be capitalized (unless you are talking about Louis Braille, in which case the normal rules for proper nouns apply).

- Some braille readers can read up to 400 words per minute. The average reading speed for sighted readers is around 250 words per minute.

- There are 64 possible braille characters, including all dots being flat (which is a space, and works the same way they do in printed text).

Blind etiquette: nine ways to be considerate when interacting with people with visual impairments

(Courtesy of Perkins School for the Blind and Teaching Students with Visual Impairments)

There’s no “secret” to interacting with people who are blind. They just want to be treated like everybody else, with courtesy and respect. While not all of these tips are appropriate for social distancing today, we all look forward to a time when we can offer our arm for assistance in the future.

Here are nine suggestions that will make your next interaction with someone who is blind more respectful of them and more comfortable for you:

- If you think someone who is blind may need help navigating, ask first. It’s jarring for anyone to be unexpectedly grabbed or pulled, but especially so for someone who can’t see who’s doing the grabbing. By asking, you give the person a chance to accept or decline your help. If they decline, respect their wishes and do not try to help anyway.

- If your help is accepted, offer your arm, tell the person you have done so and allow him or her to grasp your arm just above the elbow. That makes it easier for the person to feel your movements and follow on their own terms. Let them know about approaching hazards such as stairs or narrow passages.

- If you see someone who is blind or visually impaired in imminent danger, be calm and clear when you warn the person. Use specific language such as “there’s a large pothole right in front of you,” or “the sidewalk in front of you is blocked for construction” instead of “watch out!” Also, use directional language such as “to your left” or “directly behind you” rather than “it’s over here.” Remember that using directions in relation to other things doesn’t work for someone who can’t see those other things.

- Identify yourself when approaching someone who is blind, or when entering a room with them. Even if the person has met you before, he or she may not recognize you by your voice. In a group setting, address the person by name so they know when you’re talking to them. Let the person know when you depart, so they don’t continue the conversation to an empty room.

- Never pet or distract a working guide dog. These dogs are busy directing their owners and keeping them safe. Distracting them makes them less effective and can put their owners in danger.

- While it is possible for people with visual impairments to also be deaf or hard-of-hearing, this is not a given. Approach unfamiliar people with visual impairments as you would sighted people, and avoid raising your voice unless you are asked to.

- Speak naturally and don’t feel you need to change your vocabulary when you talk. Don’t be afraid to use words that refer to seeing. Phrases like, “Do you see?” and “Look at that!” are common expressions that everyone uses.

- Treat adults with visual impairments like adults. Having a visual impairment does not interfere with cognitive abilities or prevent someone from participating in society in age-appropriate ways.

- Consider using “people-first” language and take personal preferences into account. While many institutions often use people-first language (i.e., “a person who is blind” rather than “a blind person”), many are reclaiming the word “blind” to describe themselves freely and proudly. Respect a person’s preferences and learn about the work being done to separate the word from negative connotations and stereotypes.