Behaviorism, measurement, and learning

One of the real benefits of defining learning as a change in behavior, the way Behaviorists do, is that behaviors are easier to measure than cognitive changes tend to be. In fact, Behaviorism itself was developed in response to earlier psychological ideas that placed a heavy focus on what happens inside the mind of the learner. Early behaviorists like Watson didn't even believe that learners had an internal life that was separate from their expressed behaviors. B.F. Skinner, whose ideas are quite influential in education even today, did believe in the existence of the mind, but he argued that the individual mind is a black box and inherently unknowable, and therefore it's better to focus on behaviors than cognitive development.

Yet Behaviorism has its challenges as well. There are not many people who are likely to agree that their own lives are simply a collection of actions: responses to stimuli (particularly, external stimuli).

So we have a tension here: on the one hand we have the rich and personally-validating idea that knowledge is constructed, and on the other hand we have the argument that internal realities, whether or not they exist, are at best secondary to actions. Both can certainly be useful constructs, and we can surely use both of them simultaneously in our attempt to understand learning and teaching, but each construct has its supporters and challengers, and sometimes they disagree.

At the same time, practical educators must have data to measure the efficacy of their techniques and programs. The reality is that when it comes to data, the easiest thing to measure are behaviors. Cognitive changes, being internal to individual minds, are much, much more difficult to get at.

As a consequence, practical education tends to focus heavily on measurable goals that are linked to behavioral change. There is a focus on creating educational goals (often called "outcomes") that use only "measurable" verbs. For example, a measurable course outcome could be, "students in this course will be able to list five learning theories and explain their historical significance to the field of education." Students can be measured when they "list" the theories and can be evaluated for accuracy when they "explain" their historical significance. In fact, an entire course or program assessment can then be built around how well students who complete the course can do those things. The measurement of those student actions becomes very important data for the program. This is not the only learning that happens in any course, but it is learning that can be easily measured and reported.

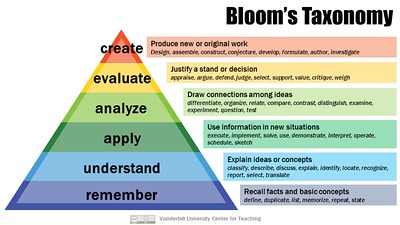

Educators also need these measurable verbs to be useful for all kinds of education, from the most basic tasks like memorization, to much more challenging tasks like creation and invention. To meet this need, most educators turn to "Bloom's Taxonomy," a "pyramid" shaped model that organizes learning from the most basic tasks (remembering something) to the most challenging (creation). Bloom's taxonomy was originally developed in 1956 by Benjamin Bloom and his collaborators, and it started to become especially influential in the late 20th century and into the early 21st. Bloom's Taxonomy can be depicted visually this way:

You can read more about Bloom's Taxonomy and see lists of verbs associated with each level of learning on this "taxonomies" page at the Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning.